Changing the way we look at street homelessness in railway stations

Posted: 7 July 2022 | Lucie Anderton | No comments yet

Lucie Anderton, Head of the Sustainability Unit at the UIC, explains the evolving role that train stations play as public spaces, and how these changes can benefit the growing street homelessness issue.

Train stations are unique public spaces which are often open all day, every day, and are connected to other public spaces and to other transport modes. Stations and trains offer people who are vulnerable and street homeless basic services such as toilets, shops, and a safe place to meet or seek help. People presenting as homeless at train stations report significant feelings of safety, though less so at night, and give their motives for coming to a station as social reasons, ‘begging’, ‘warming up’, ‘passing time’ or contacting a social service organisation1. Homelessness is a growing issue in many countries worldwide. It is estimated2 that around 150 million people worldwide are homeless, which equates to approximately two per cent of the global population, and the visibility of people observed sleeping rough around the railways is increasing.

Contrary to perception, the street homeless who are living in and around stations are more likely to be the victims of crime rather than the perpetrators.

The role of the railway station is changing in many cities, becoming more than just a place to get on and off a train. Stations have a growing commercial role, with increasing retail and leisure activities; this changing role is accompanied by a much greater focus on customer experience. Station managers are coming under increasing pressure to act on anything that might impact the perception of security and comfort in our stations. The presence of marginalised people and people sleeping rough in train stations is considered to present a multitude of problems in terms of sanitary conditions and security. Contrary to this perception however, the street homeless who are living in and around stations are more likely to be the victims of crime rather than the perpetrators. Nevertheless, their presence has an impact on passengers’ feelings of security and there have been incidents of both verbal and physical assault on station workers. Customer service staff are spending an increasing amount of time in ‘hotspot’ stations engaging with street homeless. Previously, station staff have had very little training on how to best communicate with these vulnerable people, who often have very complex issues. There is a reputational issue too; reports of unsympathetic approaches to homeless people have been covered in social media and press, showing railways in a negative light. However, where people are starting to take a new, responsible and proactive, approach, there has been a lot of positive attention and public interest.

Talking with members at the ‘Inclusive Stations Working Group’, the UIC has found that many station managers no longer wish to carry on with older ways of doing things, where they would try to move people on. This simply does not work and so they are now trying novel approaches and developing more socially responsible policies. Looking at members who have reported successful initiatives, the UIC has found some common themes with key factors that are starting to really stand out.

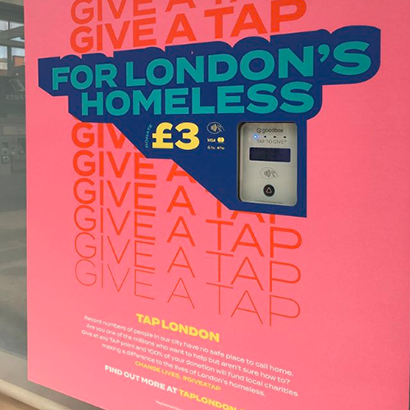

Credit: Network Rail

The first lesson learnt is the value of having a defined and documented policy that gives clear direction to staff and stakeholders. The best policies have specific goals, have been informed by experts working closely with the homeless community, and are supported by a wide range of other railway or civic society actors. In the UK, a pan-industry charter has been signed by the national government, railway operators, British Transport Police (BTP) and the infrastructure owner, Network Rail. The charter has support at the highest level and sets out clear intentions around a safeguarding approach and specific commitments on training and reporting.

A policy document is only useful however, if it is well understood and the workforce have the tools to implement it. Awareness raising initiatives can help staff to better understand the situation of the people they are encountering, to challenge negative perceptions and to build empathy, particularly if the training is participatory and involves people with lived experience of homelessness. With good training, staff can be better prepared to engage homeless people and to know where or how to seek expert support.

In 2012, The ‘HOPE in stations’ project was able to demonstrate the value of training. This European Commission (EC) funded research proved the clear advantages and value of training operational station staff with other station stakeholders. The project coordinated staff training across three large European stations: Paris Nord, Brussels Midi and Roma Termini, and all participants reported very positive feedback on the training experience and the value it brought to them in their roles at stations.

Not all stations, cities or people are the same, and understanding individual key issues can help design a solution that is appropriate and effective.

Another indicator of success is the effective use of data and its power in improving the impact and communication of benefits. Not all stations, cities or people are the same, and understanding individual key issues can help design a solution that is appropriate and effective. Improving data collection on the issues and impacts on the railway can help better direct resources to address important issues. Agreeing how information is shared across multiple stakeholders within a city can help build a more joined-up approach, and simple signposting of information for staff can be helpful to direct those in need to support services. It is becoming common to collate and analyse data to observe trends. In the case of Network Rail, the impact of their initiatives was measured using ‘social return on investment’ calculations, demonstrating the case for investment and continued support. In Canada, Via Rail Police have a ‘Vulnerable person plan’, the goal being to work together to find ways to help vulnerable people out of homelessness. Data showed that of the vulnerable people encountered in 2021, 21 per cent had been referred to services and, on a yearly basis, an average of 10 people had found housing and employment through the programme.

In Italy, a Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane (FS) project, the National Observatory on Solidarity in railway stations (ONDS), set up its first Help Centre at Roma Termini in 2002. The project created a specific space to support the homeless and marginalised people in and around the station environment. The success at Roma Termini has meant an expansion of the initiative across 18 Italian railway stations and a working think-tank, where studies, strategies, analysis, data and best practices are shared and developed, in order to make social intervention more effective.

Underpinning all these successful projects is a spirit of collaboration and cooperation. Many actors can become stakeholders in homelessness at stations, including local authorities, police and NGOs/charities. Treating the station in isolation, rather than as part of a wider community, misses opportunities for working more effectively and efficiently. For Jernhusen, Sweden, a structured approach was taken to create a safe, secure and attractive station for all. As a first step, data was collected to better understand the issues in the local area, local challenges were identified and documented, which were validated through joint effort with local stakeholders. Goals were then formulated, and a full range of tools employed: policing styles such as CCTV for criminal behaviour hotspots; station design measures that discourage anti-social behaviour, including seating choices, and social measures to support vulnerable people, such as access to medical services. An important part of the success achieved through this approach was working with specialised actors who had a strong local anchoring.

In Strasbourg, France, SNCF has a long-established (since 1998) system called ‘Point Accueil Solidarité’ (PAS) in place at Strasbourg station to support social inclusion and homelessness. Dedicated social workers are based close to the station, and welcome street homeless and vulnerable people to offer advice and support accessing services including health care and accommodation. Before the pandemic, the centre received an average of 100 people every day.

A system called ‘Point Accueil Solidarité’ (PAS) is in place at Strasbourg station to support social inclusion and homelessness. Credit: SNCF Gares et Connexions.

Indian Railways has focused on helping the very vulnerable juveniles and children encountered on the railways and at stations. Their strategy includes the promotion of a ‘Railway Helpline’ to report the presence of vulnerable people and a ‘Standard Operating Procedure’ to effectively handle children in distress. A collaboration with the Ministry of Women and Child Development has been set up to establish 132 ‘Child Help Desks’ across the major stations in India. As a result of this focus on protecting vulnerable young people, thousands of children have been saved from victimisation and rehabilitated: 9,969 in 2021 alone.

The conversations at the UIC working group have made it clear that railways can be powerful actors in delivering social value far beyond the core of operating railways. Rail actors can enhance their reputation while better managing a growing operational issue. Railway organisations may not have all the expertise nor licence to solve all homelessness, but through working with others an important difference can be made which benefits railway companies, their customers and the wider community.

Acknowledgments

Thanks go to all UIC members contributing case studies, including:

-Gianni Petiti (Osservatorio Nazionale della Solidarietà nelle stazioni italiane – ONDS) (Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane)

-Kathleen O’Malley (Network Rail)

-Michele Boehm (SNCF GARES & CONNEXIONS)

-Paul Van Doninck (Jernhusen)

-Jean-Ernest Celestin (VIA Police)

-Manuel Seidl (ÖBB Public Security)

-Venkateshwar Rao (Railway Protection Force, India)

References:

- Alexander Kesselring, Andreas Bohonnek, and Stefanie Smoliner, ZSI. HOPE in Stations Final report, March 2012

- According to World Economic Forum

Related topics

Passenger Experience/Satisfaction, Regulation & Legislation, Safety, Security & Crime Management, Station Developments

Related organisations

British Transport Police (BTP), European Commission (EC), Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane (FS), International Union of Railways (UIC), Jernhusen, Network Rail, ÖBB, Railway Protection Force India, SNCF, VIA Police