Portuguese high-speed rail business model: a new way forward on PPP

Posted: 17 September 2010 | | No comments yet

1 June 2009 marks the day, exactly 12 months after the international Public-Private Partnership (PPP) tender for the Poceirão–Caia high-speed rail line (HSRL) was launched, when best and final offers were in and the procedure which would lead to a successful financial close on 8 May 2010 was initiated.

1 June 2009 marks the day, exactly 12 months after the international Public-Private Partnership (PPP) tender for the Poceirão–Caia high-speed rail line (HSRL) was launched, when best and final offers were in and the procedure which would lead to a successful financial close on 8 May 2010 was initiated.

1 June 2009 marks the day, exactly 12 months after the international Public-Private Partnership (PPP) tender for the Poceirão–Caia high-speed rail line (HSRL) was launched, when best and final offers were in and the procedure which would lead to a successful financial close on 8 May 2010 was initiated.

These were troubled times in the international financial markets but the Portuguese PPP sailed through unharmed and reached what is widely regarded as an extremely cost-efficient conclusion, setting the trend, it is hoped, for a string of high-speed rail line PPPs in Portugal, namely the very important Tagus River HSRL/Motorway Crossing and the all innovative HSRL Signalling and Telecommunications PPP.

One often hears that PPP tender procedures last for a very long time and that sponsors and banks lose interest when confronted with other more speedier processes, but the Poceirão–Caia HSRL tender proved beyond doubt that it is possible to launch, negotiate and close a PPP as complex as this – moreover because it was the first ever in Portugal to deal with high-speed railways – in under 18 months and still allow for unexpected events, such as a 5-month pause under a political decision to hold everything until the October 2009 general election was over.

More importantly, the Poceirão–Caia HSRL tender was immune to the financial crisis looming in the horizon all throughout the entire procedure, proving the strength of the business model designed by the Portuguese Government under RAVE’s advice.

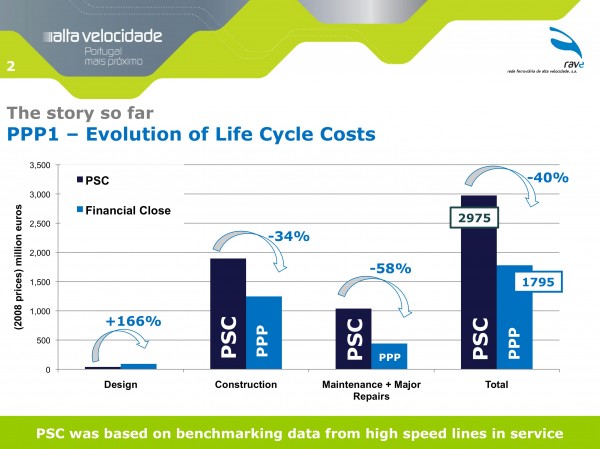

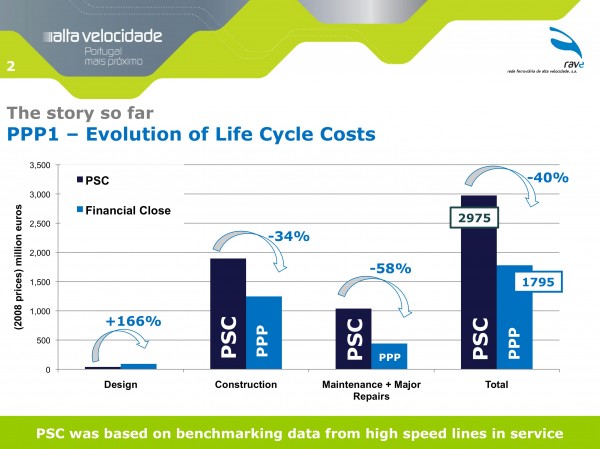

Figure 1 Evolution of life cycle costs

What is the secret behind Portugal’s success?

First and foremost, a business model which was received with wide satisfaction by all construction maintenance and financial players, soaring still after some unfortunate experiences elsewhere in Europe: five substructure and superstructure DBFMT PPP, each responsible for an average 150km stretch of high-speed rail; one S&T DBMT PPP, designed to incorporate all high speed signaling and telecommunications.

Secondly, a risk allocation structure which distributed risk where it would be understood and managed efficiently and could therefore be maintained throughout the tender process, but still flexible enough to accommodate for corrections where and when they were required. Table 1 identifies some of the most important risks and the way they were split between State and private parties.

| Risk Description | State | Sponsor |

| Inflation Rate risk | X | X |

| Financing | X | |

| Timely availability of EU funds | X | |

| Euribor variation risk (BAFO to closing) | X | |

| Euribor variation risk (closing to end of construction) | X | |

| Euribor variation risk (end of construction to end of concession) | X | |

| Design risk | X | |

| Environmental risk | X | |

| Archeological risk | X | X |

| Site conditions | X | |

| Expropriations | X | |

| Labour and materials cost increase | X | |

| Technological risk | X | |

| Construction risk | X | |

| Interface risk | X | |

| Construction delay risk | X | |

| Late availability of rolling stock | X | X |

| Availability risk | X | X |

| Traffic risk | X | X |

| Maintenance risk | X | |

| Electromagnetic compatibility | X |

Thirdly, a negotiating team which had prepared for years for this moment and was more than up to the challenge, allowing for fast and innovative responses to changing financial market conditions and to the technical, financial and legal challenges of this particular project.

In fact, the Poceirão–Caia HSRL PPP is probably the best-prepared Portuguese concession project ever.

The key political decision was incorporating RAVE in the year 2000 as a dedicated think-tank, which should be rightly credited with having saved tens of millions of Euros of public funds by preparing detailed preliminary studies made available to all interested parties well before the tender was launched and thus paving the way for a better understanding of project risk by private sponsors – ensuring extra non-apparent but very relevant savings in their final bids.

RAVE was also essential in providing technical support to the public tender jury – led by one of the most competent railway experts in Portugal, fully in line with the PPP way of doing things – allowing it to comment on bidder proposals leading to savings of 33% on construction costs and 58% on maintenance and major repair costs by reference to the public sector comparator, built exclusively on benchmarking data from other high-speed railway lines in operation.

As a consequence, the Poceirão–Caia HSRL proudly boasts a record €7.5 million/km in construction costs and an all time low of €67.000/km in maintenance costs (major and current maintenance). Figure 1 on page 101 shows how this was accomplished.

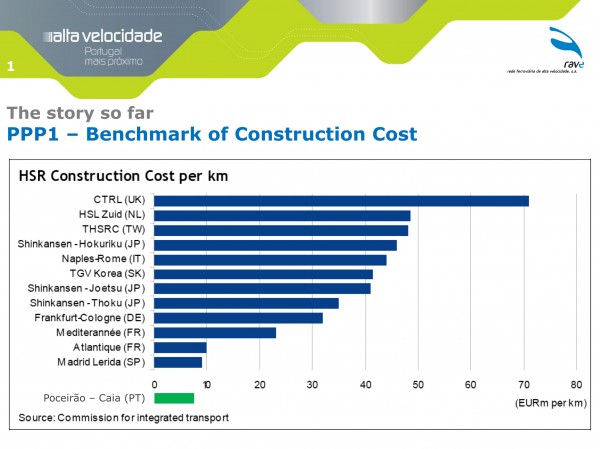

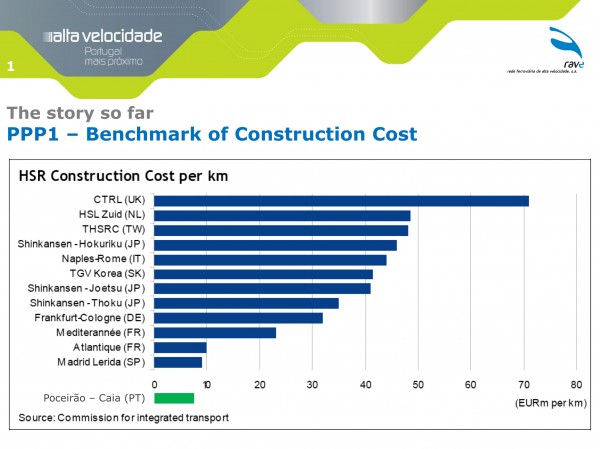

Figure 2 shows how the final construction cost for the Poceirão–Caia HSRL compares to other existing high-speed railway lines.

Figure 2 Compared construction costs

All-in-all, RAVE put up an impressive display of technical, financial and legal expertise, making it possible for the public sector to always be one step ahead of private sponsors throughout the whole tender process up to financial and contractual close. Indeed, a final exuberant push in dealing with indexrate variation risk actually saved an extra €60 million in NPV for Portugal.

Fourthly, a successful allocation of EU funds, lowering the overall required commitment of commercial banks to a fraction of what would otherwise be expected, an effect which was further enhanced by EIB’s decisive participation, taking in project risk at around half of its commitment.

It is true that the State has had to put up collateral in respect of some €300 million worth of EIB funds, but this requirement is in line with current turmoil phase terms and conditions where banks will ask the public sector for political commitment signs rather than really riskeliminating mechanisms. And it cannot be said that there were no risks to be dealt with. The way the contract addresses them is simple to lay out.

Public sector payments will come from availability payments, EU funds and REFER (the State owned infrastructure manager) commitments, with a small – probably no more than 2% – influence on payments coming from actual trains per km using the line.

The concessionaire is allowed no extra significant revenues. He is in fact almost entirely dependant on availability payments being due to it, so maintaining the line constantly available is paramount and this is precisely where more negotiating around finetuning legal texts was needed.

The question was that legal texts had to be drafted so that the testing and acceptance criteria for the HSRL are defined to accommodate the conflicting views of the State and of the sponsors and to allow for the beginning of the availability payments at a determinable point in time.

Where the State would seek the freedom to accommodate testing criteria which are not yet fully defined both internally and in the EU, passing over to the private sector the risk of varying technical rules, the private sector would ask for a battery of acceptance tests clearly and meticulously defined as from day one.

In the end, a compromise solution was reached where setting up testing routines will occur in the future within a set of looselydefined but precise enough parameters included in the concession agreement.

Another topic of negotiation included defining the scope of archeological risk taken on by the concessionaire, where a world premiere model was tested to a very satisfactory outcome.

The drafting of the tender documents on this particular subject was very aggressive, basically transferring over to the private sector all archeological risk, under the assumption that when building a 150km long, 15m-wide structure (even a very rigid structure such as a railway line, where no sudden twists and turns in layout are possible), it is possible for the concessionaire to manage the occurrence of archeological findings so as not to delay the overall construction deadline, which is really all that matters in respect of the construction phase.

This aggressive drafting, well supported in Portugal’s past experience in the motorway PPP programme, where relevant findings were unearthed almost in every case with essentially zero influence in cost and time but a more mainstream drafting resulted in timeconsuming pointless skirmishes over financial rebalancing and private sponsor diligence, was thought to be a little too aggressive by the financing banks, and was finally tuned down so that the State retains a small fraction of archeological risk, far smaller than what it used to be standard in past PPP, and the concessionaire is contractually motivated to deal with archeological findings as efficiently as he can.

Adopting long-established Portuguese PPP’s practice in expropriation risk, by basically transferring all of it to the private sponsors, also went down well with the financing banks, which have long understood how and why this may be better managed by the private sector, at lower overall indemnity values.

Probably one of the most interesting debates was on the issue of index-rate variation risks.

Both final contenders presented their BAFO proposals under the assumption that they would only take on this risk, using the standard hedging agreements their banks would in any case force them to enter into, up until the end of construction phase. After that, they both assumed that the State would take on this risk.

This was a first in Portugal, as usually the private sponsors hedge out all or a very high percentage of this risk through hedging or swap agreements.

However, the current financial crisis having caused long-term swap rate curves to be so much different from their short term equivalents, private sponsors were at a loss to still be able to present bids under the public sector comparator cap and take on all of the index-rate variation risk.

On the other hand, the State was willing and possibly eager to accept to manage this risk long-term, since the potential gains were thought to be relevant in respect of the BAFO NPV and still small and manageable enough so that in an all-loss situation the State would be able to smooth out the eventual increase in payments relating to this PPP.

A Slavic sounding acronym – AREVITJ – was then used to name a complex agreement under which the State has the ability to control and define the concessionaire’s hedging strategy – within a given set of parameters, including notional amounts and target rates – after year five, ensuring the financing banks that the State will act, regardless of the specific mechanism, if any, which it instructs the concessionaire to enter into at any point in time, as a shadow hedging party, topping up or collecting interest amount differences resulting from fixed and varying interest rates, either through direct payments or by adjusting availability payments.

EIB’s participation in the project was a key factor to its success, ensuring that on the financing side too there was a certain degree of technical expertise on HSRL projects, both successful and less successful.

Addressing EIB’s concerns over the technical competence and financial muscle of the private sponsors to successfully manage the HSRL over the entire 40-year length of the concession contract was the final hurdle that had to be overcome and where a profound debate on the nature of public sector controls over railway infrastructures – either from safety, security or infrastructure management perspectives – was deepened to a point where an easy solution was in the end found where the EIB and the private sponsors could find solace.

This debate was in fact particularly useful also from the point-of-view of the public sector, because it allowed for a set of ideas encompassing the role of REFER as infrastructure manager and dispatch operator and of IMTT – Instituto da Mobilidade e Transportes Terrestres, I.P. as regulator and systems safety authorisation issuer to be better defined at a point in time where systems safety authorisation procedures and protocols for HSRL are still being refined and adjusted throughout Europe and where the relationship between privately-built and maintained highspeed railway lines and the regulators and dispatch operators requires closer definition.

Construction activities on the HSRL stretch between Poceirão and Caia, close to the Spanish border, will begin by the end of 2010. Now is the time when all carefully drafted clauses will prove their worth. One cannot help to think that having learned from other countries mistakes in their own high-speed railways and having set up RAVE a long time ago to prepare for this moment, Portugal is well equipped to deal what whatever will happen.

So, it seems, think other European and non- European countries, many of which have asked RAVE for details on the Portuguese business model and experience-sharing, a request which it has only been too keen to accommodate.

About the Authors

Isabel Falcão de Campos

Isabel Falcão de Campos graduated from Lisbon Law University in 1987, and took a post graduation in Public Law, at the same University, in 2000. Between 1988 and 1998, she was a lawyer at two of the most important law firms in Lisbon, Jardim, Sampaio, Magalhães e Silva and Vieira de Almeida e Associados, where she had the opportunity to work with the first Projects Finance and PPP concluded in Portugal. In 1998 she joined the new railway regulator, Instituto Nacional do Transporte Ferroviário (now IMTT), leading the team responsible for the legal aspects related with railway transport concessions. Since 2006, Isabel Falcão de Campos is responsible for RAVE’s legal department and has been involved in all of the process for tendering the concession of the high-speed railway infrastructure as a PPP.

Pedro Leite Alves

Pedro Leite Alves graduated in 1985 from the Lisbon Law University, where he taught Tax and Constitutional Law for three years from 1984 to 1987. He also taught Political Science and Constitutional Law in the Autonomous University of Lisbon for two years between 1985 and 1987 and has an extensive curricula in addressing seminars in Project Finance, Administrative Law and Concession Agreements. After joining the prestigious Portuguese law firm Jardim, Sampaio, Magalhães e Silva in 1988 and having worked at Citibank, ABN AMRO and Banco Bilbao Vizcvaya Argentaria, he became senior partner in charge of the Project Finance and PPP Department in 1995. He has led legal advice teams acting for the public and private sponsors in more than 20 PPP and concession agreements public tenders ranging from road, to health, power plants, water distribution and treatment and railway infrastructures, since 1995 and up to the 2010 Poceirão–Caia HSRL. He has also advised the public sector on more than 12 PPP on-going concession agreements in Portugal.