MACs for infrastructure operation, maintenance & renewal

Posted: 26 September 2007 | | No comments yet

A multi-annual contract (MAC) for rail infrastructure operation, maintenance and renewal is an agreement between the government, as a key funder of the infrastructure, and the infrastructure manager. It sets out the funding the government will provide over a number of years and what services and outputs the infrastructure manager will provide in return for this.

A multi-annual contract (MAC) for rail infrastructure operation, maintenance and renewal is an agreement between the government, as a key funder of the infrastructure, and the infrastructure manager. It sets out the funding the government will provide over a number of years and what services and outputs the infrastructure manager will provide in return for this.

A multi-annual contract (MAC) for rail infrastructure operation, maintenance and renewal is an agreement between the government, as a key funder of the infrastructure, and the infrastructure manager. It sets out the funding the government will provide over a number of years and what services and outputs the infrastructure manager will provide in return for this.

Experience with MACs varies across Europe, but taken as a whole MACs represent a relatively new and improved way to organise the relationship between the government and the infrastructure manager. MACs replace the traditional means of organising the relationship, whereby government funding is determined on an annual basis and can be unduly influenced by the government’s other priorities and its annual budget process. Britain has gained significant experience with the concept of MACs since the separation of ownership of train services and infrastructure and privatisation of the industry in the mid-1990s.

Rail infrastructure assets are characterised by their long lives and the requirements for significant expenditure for their operation, maintenance and renewal. Optimal asset management planning can therefore only take place where there is a stable and predictable long-term framework, which in turn requires secure and sustainable funding.

The access charges paid by train operators across Europe for use of the infrastructure do not cover all of the infrastructure related costs. The residual expenditure requirement is largely covered by direct government financial support. The European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT) reported that (in 2004) the levels of cost recovery across Europe (including Eastern Europe) varied widely from just a few per cent to full cost recovery. For the 23 countries included in the study 18 recover less than 70% of the infrastructure costs from access charges, with 11 recovering 30% or less. By itself this need not necessarily be a problem if the government support fully and consistently covers the shortfall.

However, infrastructure managers have traditionally been funded on a year-to-year basis by governments and when confronted with a range of competing demands and with budgetary pressures funding for rail infrastructure has suffered. Whilst it is often possible to patch and mend and ‘sweat the assets’ for a short time, this only postpones the time when more expensive heavy maintenance or asset renewal is required. The Community of European Railways and Infrastructure Companies (CER) and the European Rail Infrastructure Managers (EIM) say that there has been significant underinvestment in rail infrastructure over the last few decades necessary to maintain networks in steady state.

Multi-annual contracts

With much of the funding for infrastructure throughout Europe looking set to continue coming from governments, the focus is on them to commit to long-term support. Hence, there is an important need to formalise the arrangements between governments and infrastructure managers, to provide both certainty and sufficiency of funding for infrastructure operation, maintenance and renewal over a number of years. Hand-in-hand with the commitment to provide funding is the obligation on infrastructure managers to achieve agreed levels of performance and other outputs (e.g. asset condition and serviceability) and to improve their efficiency. The advantages of MACs have been recognised by CER and EIM, as well as ECMT and the European Commission.

Besides being a logical way of managing infrastructure, the need for MACs is underpinned by the requirements of the EU directives (most notably 2001/14). These include, in particular, obligations for separation of infrastructure management and train operations accounts (there is no legal requirement for complete organisational separation, although this has happened in many countries) and the requirement that “under normal business conditions and over a reasonable time period the accounts of an infrastructure manager shall at least balance income from infrastructure charges, surpluses from other commercial activities and state funding on the one hand, and infrastructure expenditure on the other” (2001/14, article 6). The additional requirement of directive 2001/14 to establish an independent regulatory body, whilst not itself strictly necessary to facilitate MACs, is an appropriate way to establish and manage them. This model is the basis of the regime for MACs in Britain, discussed further below.

The Commission has recommended that member states use MACs to regulate the relationship between the state and the infrastructure manager but it does not prescribe how to implement them. MACs can take different legal forms. The MAC does not need to be a formal contract and it is important to note that the EU directives do not require MACs and that there is no single best way of implementing them. Consequently where they are used in Europe their form and duration varies. Typically they are around five years in duration but there are exceptions, for instance the Danish government has recently committed to a seven-year agreement with Banedanmark for significant investment in the network. The Commission’s Directorate-General for Energy and Transport held a workshop on MACs in 2006, has undertaken a study to examine good practice in establishing and managing them, published a consultation on MACs in July 2007 and is planning a future communication on MACs.

Regulating the multi-annual contract

The regulatory body could be best placed to establish and oversee the MAC, particularly if the regulator is independent of government and hence able to ensure fair and transparent treatment of both parties to the MAC as well as other interested parties. In order to develop and oversee effective MACs there needs to be a high-level of expertise in the regulator. Successful MACs will also depend on good information about the infrastructure condition and capability, and the costs of managing it, in order to establish a baseline and hence agreement about improvements and the funding for these. Some form of monitoring, at least on an annual basis, is required to provide information on the infrastructure manager’s activities to government, and also to train operator customers and the wider public. Publishing the results of the monitoring activity provides welcome transparency and, by itself, provides reputational incentives on the infrastructure manager to achieve at least the requirements in the MAC.

Where the infrastructure manager falls short of its obligations in the MAC then there needs to be some form of enforcement mechanism, which can include a requirement to produce a recovery plan and financial penalties. The role of financial penalties and the use of the proceeds from any penalty needs careful thought; amongst other things it will depend on the corporate form and financing arrangements of the infrastructure manager. There also need to be mechanisms for dealing with risk and uncertainty and the possibility to re-open the MAC in the face of cost or revenue shocks, outside the control of the infrastructure manager. One way to handle such shocks is to allow the infrastructure manager to establish a risk buffer. Last but not least a good MAC should provide incentives to the infrastructure manager to improve their performance and efficiency.

A key role for a regulator is to protect the legitimate interests of private sector investors who might make significant investment in long-lived capital assets in the sector, such as train operating companies. The regulator should also ensure that the industry is immune from the short-term political pressures and the electoral cycle. Whilst government has a key role in setting the overall strategy and as principal funder of railway infrastructure, this role needs to be formalised and placed in a long-term context. Clearly, therefore, this model requires commitment by government and the acceptance that, for the longer-term benefit of the railway, it may be constraining its influence in the short-term. Government must refrain from micro-managing delivery, which is a job best left to the industry.

The regulator needs to be a credible counterpart to the infrastructure manager and other interested parties, requiring it to employ or have access to engineering, operational, financial and economic expertise. It should be transparent in its decision-making process and set out for consultation its key decisions. However, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to regulation and all regulators need to be aware of practice elsewhere and be prepared to learn and adapt.

Experience in Britain

British Rail was privatised in 1996. It was split into a large number of organisations, including a separate infrastructure manager (initially Railtrack and, since 2002, Network Rail), passenger and freight train operating companies, and an independent regulatory body to oversee the infrastructure manager and its dealings with the train operators (the Office of Rail Regulation, known as the Office of the Rail Regulator until 2004). The industry has been subject to much change in the eleven years since privatisation caused largely by a number of major unanticipated cost increases and the subsequent collapse of Railtrack. Against this backdrop there has been significant growth of passenger and freight traffic on the network (with a more than 40% growth in passenger-kms). There has been significant public and private investment in the railway. Performance is recovering to levels observed before the Hatfield accident in 2000, public satisfaction is increasing and safety continues to improve. The costs of infrastructure management are now being brought back under control.

What has remained broadly consistent throughout all of this period is the model of MACs for the funding and regulation of the infrastructure manager. In common with other utilities privatised in Britain during the 1980s (such as telecommunications, electricity and water) rail is subject to a form of incentive based economic regulation. Under this model the regulator determines the maximum revenue the company can earn or prices that the regulated company can charge for its regulated activities and the minimum level of outputs (or service) associated with those charges for a fixed period (usually five years), though there are always certain specified conditions when the regulatory determinations may be reviewed before the end of the five year period. These five-year periods are known in rail regulation as ‘control periods’. The company is incentivised to outperform the regulatory determination, with the company, its customers and/or owners benefiting during the control period. The broad aim of this form of regulation is to spur regulated companies to become more efficient and outperform the regulatory determination, mimicking the effect of a competitive market.

Determining the revenues/charges and outputs is typically a two to three year process, known as a ‘periodic review’. At its heart this process revolves around submissions by the company of its projections for its future costs and activities and the regulator’s review and challenge of those. At the end of the process the regulator’s determinations for the subsequent control period are based on assumptions of the expenditure levels an efficient company would be able to achieve, with these projections historically lower than the company itself puts forward in its submissions.

2008 periodic review

The Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) started its 2008 periodic review (PR08) in 2005 and final determinations are planned for publication in October 2008, with the fourth regulatory ‘control period’ (CP4) running from April 2009 to March 2014.

PR08 is being conducted in a different way to previous periodic reviews in rail. It follows the new statutory processes set out in the Railways Act 2005. The key element of this is that the Secretary of State for Transport (for England & Wales) and Scottish Ministers (for Scotland) are required to provide ORR with high-level output specifications (HLOSs), setting out what they want the railways to achieve during the five years of CP4 and the corresponding statements of public funds (SoFAs) which they are making available to support the achievement of these outputs. The HLOSs, published in July 2007, cover high-level capacity, performance and safety outputs and specific major schemes. The outputs relate to the whole industry, which will require both Network Rail and the franchised passenger train operators to deliver increases in capacity and improvements in performance and safety.

Following publication of the HLOSs, Network Rail will submit its strategic business plan to ORR (in October 2007), setting out its view, following engagement with the industry, of the best way to deliver the requirements of the HLOSs, along with the requirements of other customer (e.g. freight operators) and funders. ORR will assess whether the HLOSs can be delivered with the public funds available. If ORR finds a mismatch then government has the opportunity to alter the HLOSs or increase the funding they make available. Ultimately, if there remains a mismatch then ORR determines what outputs should be delivered for the funds available. ORR’s final determinations for CP4 are planned for publication in October 2008. In undertaking its work to determine access charges and outputs ORR must take account of its statutory public interest duties. These include promoting the use of the network by passengers and freight to the greatest extent economically practicable, promoting Network Rail’s efficiency, enabling Network Rail to plan the future of its business with a reasonable degree of assurance, and not make it unduly difficult for Network Rail to finance its activities. The periodic review is conducted very transparently with significant consultation on all the key issues and decisions.

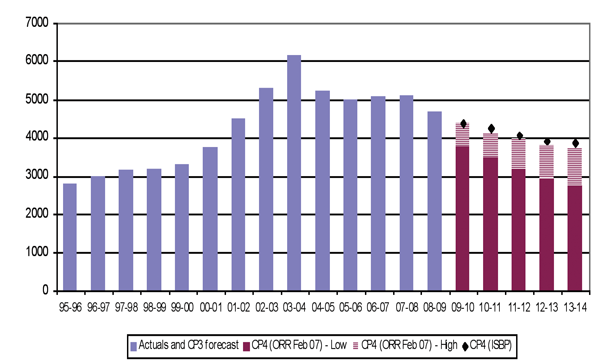

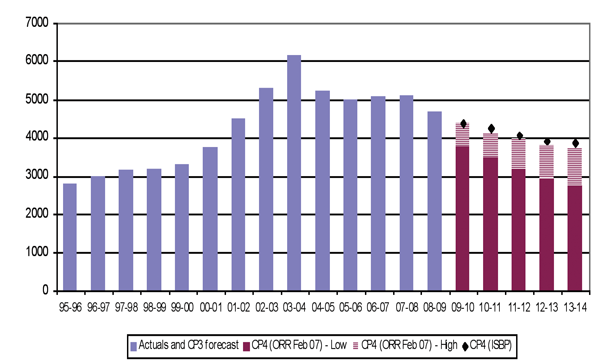

Figure 1 shows actual and forecast operating, maintenance and renewals costs on the British network since the mid-1990s. It highlights the increase in the aftermath of the Hatfield accident in 2000 and the reduction of those costs since 2004-05. The forecast for the five years from 2009-10 to 2013-14 is ORR’s estimate of the possible range for costs in CP4. It shows ORR’s view, based on the work undertaken to date in PR08, that there is potentially significant scope for Network Rail to improve efficiency and reduce costs during CP4 more than the company assumed in its initial strategic business plan (ISBP) in 2006.

In its strategic business plan in October 2007 ORR expects Network Rail to identify and justify improvements in its asset management, performance and efficiency, and identify robust plans for delivering the growth projected (with the infrastructure expenditure for these in CP4 currently estimated between approximately £4-6 billion across Britain, in addition to the ongoing operating, maintenance and renewals costs). Although Network Rail has made much good progress to regain control of its cost base and improve its performance since it took over from Railtrack there is still significant room for improvement. ORR will review and challenge the company’s proposals in order to determine the efficient level of Network Rail’s costs, taking account of the results of international benchmarking and other studies on efficiency and infrastructure costs.

PR08 is not just about assessing costs. It also includes a review of the financial framework for the company, the incentive framework it operates under, a review of the structure of access charges and reviews of the performance regime.

Conclusion

If introduced and run well, MACs should help ensure the long-term funding necessary to underpin the future development of the railways. The Commission’s interest in the wide implementation of MACs across Europe is to be welcomed. But there is no single best way to implement MACs and member states need to learn from experiences in other countries and potentially other regulated industries. Britain has gained significant experience with MACs in rail and other sectors since the 1980s. Despite the issues and changes the industry in Britain has undergone since privatisation, the regulatory regime has remained broadly consistent and provides a deep well of experience from which other countries may wish to draw from in designing MACs to fit their own circumstances.

Figure 1: Actual and forecast operating, maintenance and renewal costs for Network Rail

About the author

Paul McMahon is Deputy Director of Competition and Regulatory Economics at the Office of Rail Regulation. His responsibilities include co-ordinating the ORR’s 2008 periodic review of Network Rail’s access charges and outputs. He has previously worked as Principal Economist at Southern Water and at the consultants Atkins.