The SEA LGV concession between Tours and Bordeaux: can others follow suit?

Posted: 10 December 2010 | | No comments yet

The South Europe Atlantic high-speed line project (SEA LGV) is being built as the first railroad concession model in France. Under this model, industrial and financial partners will be responsible for building and operating the 300km-long high-speed line between Tours and Bordeaux. The contracts covering the financing of the project are scheduled to be finalised by the end of 2010.

The South Europe Atlantic high-speed line project (SEA LGV) is being built as the first railroad concession model in France. Under this model, industrial and financial partners will be responsible for building and operating the 300km-long high-speed line between Tours and Bordeaux. The contracts covering the financing of the project are scheduled to be finalised by the end of 2010.

The South Europe Atlantic high-speed line project (SEA LGV) is being built as the first railroad concession model in France. Under this model, industrial and financial partners will be responsible for building and operating the 300km-long high-speed line between Tours and Bordeaux. The contracts covering the financing of the project are scheduled to be finalised by the end of 2010.

SEA: the project

A project under study since the nineties

LGV Atlantique was the second high-speed rail line ever put into service. It was inaugurated in 1989 and has two branches – one to Le Mans and the other to Tours, putting these two cities within about one hour’s reach of Paris and making it the SNCF’s high-speed train entryway to Brittany and the Poitou-Charente region. The trains dedicated to this line run in 10 car lengths, so platforms have to be long enough, especially for double trains. They also have specific acceleration and braking capacities that call for suitable design – the grades must not be more than 2.5%. From the outset, though, they have rolled at 300km/h, while the first LGV between Paris and Lyon was inaugurated at 270km/h.

Another specific feature is that the LGV line that extends south from Tours to Bordeaux was quickly adapted to 220km/h – except on the section between Ruffec and Libourne. It was later discovered that the adaptation had been of poor quality, and renovation had to get under way as quickly as possible.

Stemming from this state of affairs is the fact that the people of the Aquitaine area are passionate supporters of extending the LGV to the south of Tours, while the people of Poitou-Charente are already well serviced from Paris and are not too enthusiastic about the idea, at least not north of Poitiers.

The Tours–Bordeaux line, also known as the ‘South Europe Atlantic HSL’ (SEA LGV), has been part of the national master plan for high-speed rail links since 1992. But building 300km of new line designed for a commercial speed of 320km/h raises an enormous funding problem – estimated at €5.6 billion in June 2006. So, to spread out the cost, the plan is to build it in two phases.

Therefore, starting in 1999, the studies and procedures for the SEA LGV focused on two distinct sections – one to the south of Angouleme and the other to the north. The former, approximately 120km-long, was declared to be in the public interest on 18 July 2006. The latter, running approximately 180km to the north of Angouleme, was declared so on 10 June 2009, when the procedure to operate it as a concession had actually already begun.

In the meantime, on 14 October 2005, the government had decided, through the Interministerial Committee on Territorial Development and Competitiveness (CIACT), to build the two sections simultaneously through recourse to a concession placement procedure.

A project with high socio-economic benefit

Construction all at once maximises the line’s socio-economic gains, because:

- It ensures the Paris–Bordeaux link will be approximately two hours, which is a threshold to achieve a market share of 90% with respect to air travel because the new line will benefit from major changeovers in travel demand that today is covered by other transport modes.

- It opens the Poitou-Charente region to Aquitaine, as it greatly reduces the travel time to Bordeaux (see Table 1).

- Starting from the trans-European axis linking the regions of northern Europe along the Atlantic seaboard to the Southwest of France and the Iberian peninsula, the Tours–Bordeaux LGV will continue with the Bordeaux–Toulouse, Bordeaux–Spain (Great Projects of the Southwest) and Poitiers–Limoges links.

- It will also free the capacities on the existing lines for regional passenger trains and freight trains, thus avoiding the risks of gradually saturating certain segments.

According to RFF estimates, the Tours–Bordeaux project could generate more than three million additional passengers per year on this route.

Table 1

| Current travel time | Travel time in 2016 | Time gained | |

| Bordeaux–Lille | 5 hours | 4 hours 28 minutes | 32 minutes |

| Bordeaux–Paris | 3 hours | 2 hours | 1 hour |

| Bordeaux–Angouleme | 52 minutes | 34 minutes | 18 minutes |

| Bordeaux–Poitiers | 1 hour 32 minutes | 55 minutes | 37 minutes |

| Paris–La Rochelle | 2 hours 50 minutes | 2 hours 27 minutes | 23 minutes |

An incomparable project on a world scale today

Building a high-speed line over 300km-long by mid-2017 means starting the civil engineering work on some 15 sites simultaneously in 2012, and will then be the largest earthworks project in progress. The following figures give the measure of this exceptional project:

- 3,300 hectares of beds

- 46 million cubic metres of excavation

- 34 million cubic metres of filler

- Some 40 overpasses totaling 9,300 metres

- Approximately 390 bridges

- 400km of roads restored

- 240 hydraulic works

- 53km of acoustic protections.

As the route passes through 12 zones classified as ‘Natura 2000’, the project calls for specific environmental measures, mainly to protect animal species that are protected at a European level. All the measures necessary to avoid high-risk zones were taken at the design phase. When the route cannot avoid the habitat of protected species, exception decrees are necessary that provide compensating measures, mainly by acquisition or management of several hundred hectares suitable to maintaining these protected species.

The specific features of the LGV extension to the LGV Atlantic also led its designers to plan putting a dual signalling system into service – ERTMS (level 2) and TVM 300 (the machine road transmission developed for trains traveling at 300km/h). This is because this line, in the perspective of opening to competition, must be able to carry interoperable trains, but at the same time, the SNCF’s TGV Atlantic trains which are equipped with TVM 300 might not yet be upgraded when the line is put into service.

SEA: the organisation

A project decided by the State in concession

The decision to build the SEA LGV as a concession and entrust control to RFF was made by the government on 14 October 2005. From the State’s viewpoint, it is a matter of introducing cost reduction and income optimisation factors that will promote the development of the French rail system, using strong competition among market players.

A concession is a well-established way of managing networks and infrastructures in France, used in the water, sanitation and waste sectors as well as parking lots and mass transit. Several major emblematic infrastructure projects have been carried out and managed in concession form: the Stade de France stadium, the Millau viaduct, the Prado-Carénage tunnel in Marseilles, the Reims light rail, as well as superhighway concessions. In the rail sector, the French-Spanish Perpignan–Figueres concession can also be cited.

The concession legal framework comes under the ‘Sapin Law’ of 29 January 1993. This was adapted to the rail sector by the law of 5 January 2006, on the safety and development of transport.

This type of contract transfers all of the project risks to the private partner (aside from a few risks falling specifically within the public sphere, such as ‘public interest’ declarations and changes in the law): design-construction, land acquisitions, maintenance and repair. Above all, it transfers the traffic risk because the concessionaire is paid first by a subsidy by the public entities during the works and also by collecting fees from use of the line by the railway companies.

Advantages of the concession arrangement

In such a ‘franchisee risk and peril’ contract, the franchisee (concession holder) takes care of design, construction, maintenance, repair, operation and financing of the infrastructure for the duration of the contract (50 years in the case of SEA). The candidate is generally selected on the basis of multiple criteria, the main ones being the amount of the compensating subsidy requested and the soundness of the bid.

These two criteria are contradictory and need to be balanced. That is, in order to reduce the amount of the subsidy, the concession candidate has to convince its bankers that the traffic will be high, so it can get larger loans and reduce the compensating subsidy requested. However, if the candidate’s bid is too optimistic, the lenders’ traffic analysts may discourage their customers from supporting the candidate. So, the system should balance itself out, with the public entity given no final guarantee against the risks stemming from the franchisee’s business.

In the case of SEA, recourse to a concession gave rise to a new process based on the ‘contributive capacity’ of all the players in the rail system, considering a traveler’s propensity to pay, as they benefit from a new highperformance transport service saving them an hour between Paris and Bordeaux, while the transporter’s economic model is adapted so it can bear higher toll rates. This modeling, which was established by RFF and confirmed by the analysts of the three candidates, led to an increase in the rate level for use of the infrastructure between Paris and Bordeaux, thereby optimising concession income.

A very long call for bids procedure

The procedure was launched by a public call for candidacies published in the ‘Journal Officiel de l’Union Européenne’ on 1 March 2007.

Three candidacies were filed on 31 May 2007. The first was based on the Eiffage company, which stood alone. The other two were filed by consortia grouped around Bouygues and Vinci, and infrastructure sectordedicated investment funds.

Considering the innovation required by modeling the franchisee’s future income, it was decided to initiate a two-round procedure, in which the first round was to test the market capacities and adapt the remainder of the consultation process to the results.The candidates were asked to return their initial bids on 15 September 2008, a date which was later to coincide with the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. Several variants of rate structures, in particular, were requested and RFF ranked 14 bids.

As the bids met RFF’s expectations, RFF did not use the option allowed in the consultation rules to eliminate one or more candidates between the two rounds.

Thus, the three aforementioned candidates were still in the running for the second round of the procedure, which was concluded by final bid submissions by all of them on 15 December 2009.

After these bids were analysed, the group consisting of Vinci, Caisse des dépôts (for which the CDC-Infrastructures investment fund was substituted during the procedure, in accordance with the rules) and AXA Infrastructure Investment was declared the franchisee in the spring of 2010, enabling the start of negotiations between RFF and the candidate.

Negotiations took less than four months, which was a relatively short time in light of the project dimensions and complexity. To follow was a period during which the contract was ironed out with the selected candidate, and this is expected to be completed in the coming days and allow contract signing before the end of 2010.

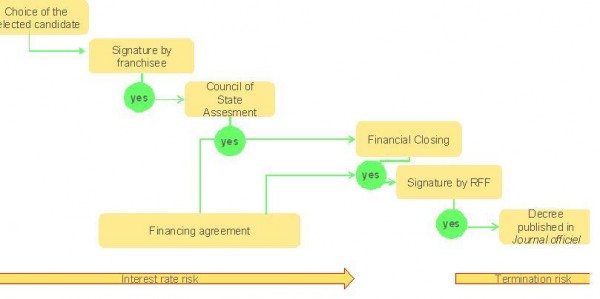

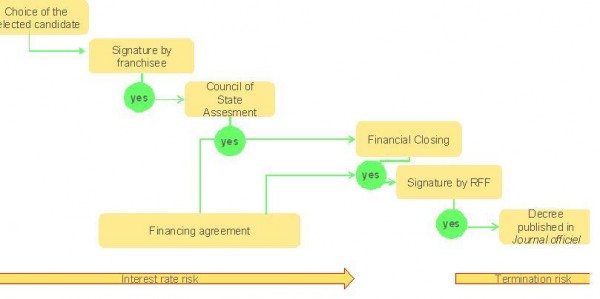

The procedure to be followed from now till signature is outlined in Figure, which shows that final contract signing by RFF will occur after the Council of State hands down its opinion, and simultaneously with the financial closing.

To make the financing arrangements possible, RFF is taking on the interest rate risk between the date of bid submission and the date of financial closing, which should occur just before the contract is signed by the franchiser. After signing, RFF bears the risk of the hedging instruments unraveling if the contract is cancelled by a court decision.

Figure 1 The procedure to be followed from now till signing of the contract

SEA: implementation

A public roundtable involving the State and 57 regional entities

In addition to the financing by private investors and banks, the SEA project, for an amount of €7.8 billion (in current Euros), calls for a compensating subsidy granted by the public authorities.

This subsidy is paid by RFF and by two types of public players: the State and all the regional entities interested in the line – that is, all the communities of the southwest located to the south of Tours who will benefit from the significant time savings thanks to the line. So, it was quickly decided to associate the Poitou- Charente and Aquitaine regions to the operation’s financing plan.

However, the Midi-Pyrenees region also benefits from the one hour gain in travel time the line offers the Bordeaux population. The regions, departments and main cities served by the high-speed trains to the south of Bordeaux, and which are interested in the SEA LGV extension in the direction of Toulouse, Spain and Limoges, were gradually brought into the project’s financing. In the end, 57 communities including five regional councils, 19 departments and 33 town or city communities are solicited by the State to conclude a financing agreement, which is a condition for RFF to sign the concession contract.

That is, RFF contributes an amount that is calculated by the financial flows (receiptsexpenses) procured by the line over a 50-year period, and cannot assume alone the compensating subsidy the franchisee is calling for. This is why it is planned that the balance of the financing should be shared on a parity basis between the State and the public co-financers. Based on receipt perspectives and optimisation brought by the concession arrangement, RFF and the negotiators of this new outsize financing agreement indicate to the co-financers that the objective sought is to reach 50% public financing (State + local communities).

The objective is ambitious. Recent LGVs have called for more than 75% public financing (before the rail reform that led to the creation of RFF in 1997, LGVs were financed by SNCF indebtedness). This will be achieved and even exceeded. Thanks to the effective competitiveness organised by the call for bids, the subsidy called for by the franchisee reduces the share of public financing to less than 44%.

Table 2 summarises the financing plan without the franchisee’s financing costs. The forecasts are based on assumed variations of a pool of representative construction cost price indices and work schedule assumptions, as well as on the interest rate level considered at the time the bids were submitted at the end of 2009.

Table 2 shows that RFF’s contribution to the project is large. It comes from the additional traffic generated on the existing network by creating the line, mainly on the Paris–Tours route, and by the rate rise anticipated by RFF on the adjacent network.

Table 2

| Forecasts on 2016 horizon | Current € millions |

| RFF contribution | 2010 |

| State and regional entities | 3426 |

| Franchisee self-financing (except financial costs) | 2380 |

| Total resources | 7816 |

| Investments made by RFF | 980 |

| Works carried out by franchisee | 6836 |

| Total uses | 7816 |

A significant part of this contribution is allocated to works that RFF is to carry out in accompaniment to the network built by the franchisee, which is mainly the intersection of the new line with the conventional line servicing the intermediate cities. These works come to approximately €1 billion (current Euros), integrating the expenditures that RFF has decided to commit by anticipation in order to reduce the franchisee’s job startup times. This consists mainly of real estate acquisitions and archeological diagnostic operations.

The rest of RFF’s contribution is paid to the franchisee to complement the public contributions, which are estimated at €3.4 billion, divided 50% between the State and the local communities, and could even be slightly less than this amount if the financial closing comes quickly, considering the current level of interest rates. The share of public financing (share of the State and of local communities in the whole investment) thus comes to 44%. The fantastic wager made by those who initiated the concession idea in 2005 is on its way to success.

SEA: a success presaging others?

There is still a lot of work to be done before the contract enters force and the works begin in 2012 for a planned service open date of June 2017. If the concession contract is signed under the conditions anticipated today (by the end of the year) it will be an indisputable success for RFF.

Coming after the 18 February 2010 signing of the largest partnership contract ever signed in France (for replacing the groundtrain analog radio system used by the national rail network with the GSM-R technology), this success will confirm that RFF is capable of using the whole pallet of major project management tools: conventional owner status for the Dijon–Mulhouse LGV, which will begin service in December 2011, and for the European LGV East extension to Strasbourg that should enter service in June 2016; public-private partnership for the SEA project concession; and the partnership contract for GSM-R.

Without mentioning that the partnership contract approach is also being followed for the Brittany–Loire country project for which the final bids were received on 13 October 2010 which makes a possible service startup close to that of SEA, and for the Nimes and Montpellier bypass construction, for which the final competitive dialog should begin next November.

About the Author

Pierre-Denis Coux

Pierre-Denis Coux is a state civil engineer and a graduate of the École Nationale d’Administration (ÉNA). After a career in the Ministry for Infrastructure where he worked on the financing of housing projects and motorways, Pierre-Denis Coux joined Ŕeseau Ferré de France (RFF) to lead the South Europe Atlantic high-speed rail project. The President and Deputy Chief Executive Officer of RFF have also appointed Pierre-Denis Coux to lead the development of the ‘Direction des Grands Projets’ (Department for Large-Scale Projects).